It is important to use the right tools for a given job. Science is no exception. In particular, given the vast amounts of data that are now routinely encountered in the field, one will want to use the best available data analysis tools (by whatever metric one prefers – ease of use, speed, efficiency, versatility, etc.)

In neuroscience, there is a prevailing sense that MATLAB currently dominates the market for analysis tools, but that Python has a lot of momentum.

To get an empirical handle on this, I decided to search Google for a stock phrase employed in the vast majority of methods sections of papers (“Data were analyzed using x”), replacing x with a variety of modern – and presumably commonly used – analysis tools. For the sake of completeness, I also search for “Data were analyzed in x” and “Data were analyzed with x”, then adding them up (although the vast majority of phrases included “using”, not “with” or “in”). And yes, this is the passive voice. Most scientists are about as well trained in writing as they are in programming…

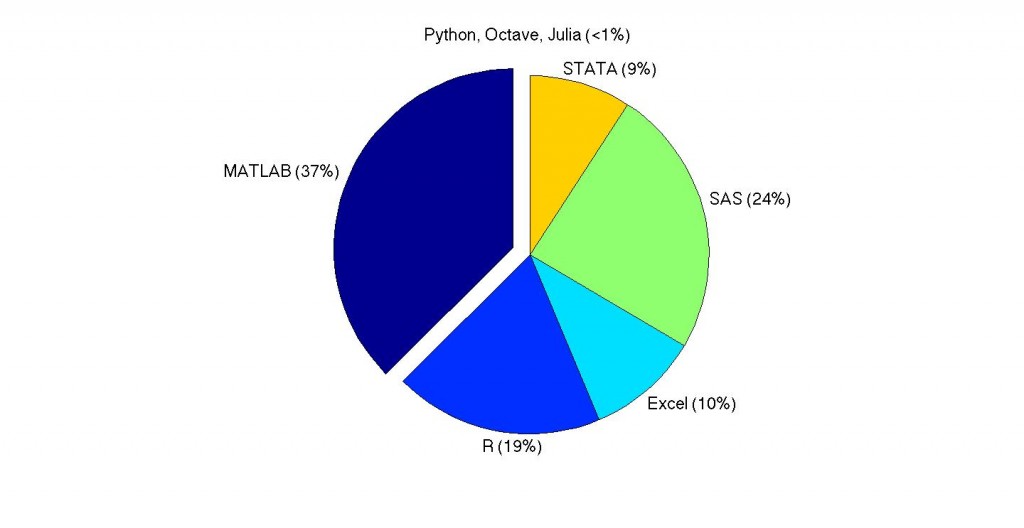

The results are below and they strike me as surprising, to say the least. A whopping 8 (in words, eight) hits for Python, 5 for Octave and none for Julia.

Results of the Google search (as of 09/26/2013). The slice representing Python, Octave and Julia together is too small to be visible. Aptly, the data underlying this figure were analyzed using Matlab.

So what is going on? Are scientists – despite all the enthusiasm for Python, Octave and Julia – not actually using these methods in published papers? Is there a systematically nuanced way of grammar usage that I am missing?

Regardless of the validity of these particular results, there can be no question that Matlab cornered the analysis market these days (at least in neuroscience – I presume the heavy use of SAS and Stata takes place in other fields).

Ironically, this is cause for concern. Success leads to dominance. Dominance leads to a sense of arrogant complacency that is not warranted in the field of technology. Just ask Nokia or the ironically named “Research in Motion”, ill-fated maker of the blackberry. Once a competitor has gained momentum because the monopolist missed “niche” developments, it is almost impossible to halt it.

To date, MathWorks has completely missed out on capabilities for online deployment of code. It is quite disgraceful actually, as this is now routinely done in Python and R. Does MathWorks have to be shamed into doing the right thing on this?

Finally, I hope we can move beyond primitive tribalism on this. I do understand that it comes naturally to people and that it is ubiquitous – be it with regards to computers (Mac vs. PC), cell phones (Android vs. iPhone), sports, etc.; however, this kind of brutish behavior has no place in science. All that matters is that one uses a suitable tool for the job at hand so that one can do the science in question and hopefully move the species forward a bit. Moreover, it is understandable that any self-respecting programmer can’t have things to be too easy or straightforward. Otherwise, anyone could do them. That might indeed be the chief problem of Matlab.

Seriously – it doesn’t matter as much which language you use to program as long as you are in fact programming. There is a simple reason for that: The success of western civilization allows for a second – heavily incentivized – route to rewards, namely social engineering (by hacking some fairly primitive tribalist circuitry). So the waves of BS can rise ever higher. But programming has to work. So the BS can only go so far. And we need more of that. More reality checks (in the literal sense), not more BS. We have too much of that as it is.

Maybe given that Python is a more general purpose programming language, people tend to report more the libraries that they used? For example, it seems that using “Data were analyzed using scipy” gives more results. Still quite small number in comparison with MATLAB.

I thought that as well, but no dice. For instance, there are *no* hits for the scipy example you give. Google only finds something if the quotes are removed (which is not the same query as for the others). What is going on?

You are right. Also, while in google “python” has more hits than “matlab”, in google scholar “matlab” is 6 times more frequent.

Indeed. And I think we’ll need to discount the Google Scholar number for Python again, as it is also a) a research animal and b) as it turns out, a surprisingly common name. I don’t think anyone is named “Matlab”. So if Python is so hot, why is it so sparsely represented in the literature? Is the revolution yet to come?

Yes. It is silly just to search for “python”. Changing it to “using python” might be a bit better. Using it in Google Trends for Science, suggests that the revolution is coming http://www.google.com/trends/explore?q=using+python%2C+using+matlab#cat=0-174&q=%22using+python%22,+%22using+matlab%22&cmpt=q

Still, despite the about the same value in 2013 in trends, in google scholar “using matlab” is 15 times more frequent than “using python” (using data only from 2013).

Using wildcards gives very different results. If you search for “Data were analyzed * python”, you get a lot of variations. For example:

“Experiments were conducted and data were analyzed using free software including AutoDock Vina, AutoDock Tools and Python Molecular Viewer”

“data were analyzed using an in-house Python ”

The corresponding matlab and python searches give 50,900,000 vs. 18,900,000 results, respectively. Matlab still has more results, but it is much closer.

Overall, I think this indicates that the search phrase just isn’t used that much. Variations on it are much more common.

Another thing I tried as searching google scholar for “python.org” (12,000) vs. “mathworks.com” (29,900). Ratios are similar to the wildcard search (2.69 vs. 2.49 in favor of matlab).

I deliberately did not report on the results of a wildcard search because that can be somewhat of a… wildcard. Specifically, wildcard searches can behave extremely idiosyncratically and downright wonky (not generalizing across users), in my experience. So when I tried to replicate your search, the 19 million estimated results collapsed to 15 when actually clicking on the pages [1 2] at the bottom of the Google search page. So I’m not convinced. Personally, I don’t care for this kind of divisive holy war. Personally, I recommend to just use whatever language works for you to get the job done and not invest too much ego and self-identity in the choice. I was just surprised by the lack of unique results. As of late 2014, I still am.