It is obvious where ideology comes from. It solves a lot of problems. A small tribe needs to agree on a distinct course of coherent action. Otherwise, its strength is frittered away, defeating the very point of finding strength in numbers, i.e. of being a tribe in the first place. Ideology also solves a lot of freerider and principal agent problems in general. It makes individuals do things for the common good that objectively impedes their subjective welfare and that they wouldn’t otherwise do. This also makes good sense along other lines. Small tribes perish or flourish as a whole (a genetically highly interrelated group), not as individuals. Ideology promotes fitness on the level that it matters, the group-selection level.

However, we no longer live in a world of small, competing, ever warring and highly xenophobic tribes. On the contrary, we live in an extremely large society, in terms of the US about 2-3 million times as large as the typical tribe, which constitutes the form of social organization that was the norm throughout almost all of human evolution (if one considers the whole world as one big globalized and highly interconnected society, it is about 70 million times as large). So the archaic model of social organization clearly doesn’t scale. Yet, its roots are still with us. For a simple test, try watching a soccer game (or indeed any team sport) without rooting for a particular team (or watch a game where you don’t care about any of the teams). The athletic display won’t be any different, but it will likely be rather un-riveting.

So in modern times, tribalism is a cancer that is threatening to tear society apart. Why? Because most of the remaining societal problems are extremely thorny and complicated (that’s why they remain in the first place – we already addressed the easy ones). They usually don’t lend themselves to resolution by experimental approaches. But a lot typically rides on the outcome, the answer to these questions. This gives ideology a perfect opening to take root. For instance, modeling the climate is extremely complicated. All models rely on plenty of assumptions, relatively sparse data and are so complex that they are even hard to debug (or to know when debugging was successful). It is very hard for anyone to ascertain what is going on, let alone will be happening in the future, yet ideologists are very keen to either dismiss any probability of warming or assume dramatic human-caused warming as a certainty. The confidence of both camps far exceeds the data cover. Where does it come from? Potential holes in the story are simply filled in by ideology. Similar questions arise – for instance – in history. A key question is history is: What makes a society successful? The most realistic answer is that it likely involves a complex interplay of geography, genetics and culture. It is extremely hard to assign relative weights to these factors, as it is impossible to do experiments on this issue. Yet, one can make a good living writing books asserting that it is all geography (implicitly or explicitly assigning a factor of zero to the other factors), all culture or – recently – by pointing out that the weight of the genetic factor is unlikely to be zero, unfashionable as it might be, given the political climate.

Which position is most compelling to you says much less about which position is true – at this point, the evidence is far from conclusive – but much more about you: Which position do you want to be true? Why would you want a particular position to be true? Because it neatly fits in with your worldview or Weltanschauung.

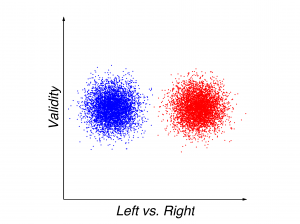

What is the problem with that? The problem is that people on the two different ideological poles simply look at the same data from two different vantage points (e.g. left vs. right, see figure 1).

Figure 1: This represents reality. Two ideological camps have positions on issues that vary along the left/right dimension. Some of them are more valid than others, but no camp has a monopoly on validity, given these issues.

But in the mind of the ideologue, any issue doesn’t come down to a horizontal difference, but rather a vertical one – the ideologue assumes that the positions in one’s camp are valid, the others invalid. But when one sincerely perceives a difference in appraisal as a difference in fact (where one is either right or wrong), resolving these issues is basically impossible.

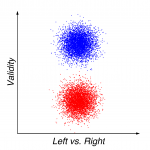

Figure 2: Liberal ideology. From the liberal perspective – which corresponds to a clockwise rotation of reality by 90 degrees – their positions are now perfectly centered in ideological terms. They just happen to be right, whereas the other camp is just wrong about everything.

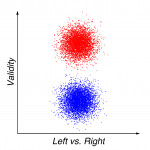

Figure 3: Conservative ideology. From the conservative perspective – which corresponds to a counterclockwise rotation of reality by 90 degrees – their positions are now perfectly centered in ideological terms. They just happen to be right, whereas the other camp is just wrong about everything.

The insidious thing is that this happens inadvertently and automatically. People that take a particular position will naturally see the other one as invalid and just plain wrong. Not as a difference in position, but as a matter of (moral) right and wrong. Righteousness vs. wickedness. Feeling this with every fiber of their being, leads to an immediate dismissal of the other position. If they can see the truth so clearly, why can’t the other side? Surely, they must be willfully ignorant, malicious or both. Ascribing turpitude usually follows. Worse, this destroys any reasoned discourse. Making a nuanced argument will go unappreciated, as the ideologue will not understand its nuance. Instead, it is automatically transformed into a low dimensional ideological space, perpetuating the framework of divisive tribalism, with all of its odious consequences. As we’ve known for a long time, it is basically impossible to convince someone with complete certainty that they are wrong, regardless of how ludicrous their position is or how much it flies in the face of new incoming information.

It is awfully convenient that the same people who disagree with us are also those who are dead wrong about everything. If the issue is important enough, (religious) long and brutal wars have been fought about this.

The problem is not to be wrong about something. That happens all the time. The problem is how right it can feel to be so wrong. If you want to experience this for yourself, there is a simulacrum with a somewhat juvenile name that deals with issues like information accumulation, cue validity, confidence and uncertainty. It allows an apt simulation of what social primates can be absolutely convinced of, even in the near absence of valid information. This can be rather scary. An important difference to reality is that in reality, there is rarely a reality check (feedback from reality or god) whether one’s beliefs actually correspond to the truth.

What is the way out of this? Acknowledging that this is going on. Metacognition allows for a possible avenue of transcending these biases. Naturally, this will take a lot of training, particularly as most actors (the media, for instance, have every incentive to be as divisive as possible in their rendering of events). But by appreciating the complexity of problems and by embracing the fundamental uncertainty inherent to life, one opens the possibility that this can be done. It won’t be easy, but there is no real alternative. A de facto perpetual cold civil war is no real alternative. Certainly not a good one.

The problem with the ideologue is that they are constitutionally unable to learn from feedback. As they already see themselves as right to begin with, the error is irreducible. As such, they are the natural enemy of the scientist. In particular, it is important not to give people a pass for being uncivil (and not helpful) just because they agree with us ideologically.

Tribalism had its day, for most of human history. And it was very adaptive. But today, it no longer is. Instead, it is needlessly divisive. Is it really useful to judge people based on what browser or operating system they use, what car they drive, what phone they have, which language they program in, etc.? People are obviously eager to self-righteously do so at the drop of a hat, but is that really helpful in the modern world (the traditional solution being to wipe out the other small tribe)?

Being more interested in “hearing and understanding” the other side of any given argument, than communicating ones own position, is the first step in resolving any disagreement.