Science is concerned with systematically probing the fundamental nature of reality, determining what is and what is not the case. In other words, science is about figuring out what is going on and about understanding how the world works (with the usual caveats about approximations to the Truth, truth conditions, etc.).

Given a desire to optimize our grasp on the system we are inhabiting, there is really no substitute for such activity. We are – individually as well as collectively – ignorant upon our arrival in this world. Reality does not come with a manual. If we want one, we have to write it ourselves. Ultimately, that is what science is all about.

However, despite a solid 400+ years of involvement of the human species in an endeavor that we today would recognize as science, there are quite a few open – and deeply haunting – questions about the nature of reality. For instance, I am still quite astonished that anything exists at all. Anthropic principle aside, it would probably (?) be much easier if there was just nothing. Of course, I am not exactly sure what complete nothingness (absence of time AND space AND energy included) would be like, but it is nevertheless quite a disturbing thought. Moreover, I am at a complete less what the “exists” in the sentence above actually entails. In other words: “What is is?” or “What in being is in being”. Philosophers like Heidegger made entire careers out of contemplating these precise questions, and I don’t think these issues can simply be dismissed as mere word games (quite a few philosophical questions can, Wittgenstein was onto something; however, I do not think this applies here). What is clear to me is that at this point, we do not even possess the adequate vocabulary to characterize these issues and perhaps not even the proper cognitive apparatus to contemplate them (this should not be surprising. Nothing in our evolutionary history suggests we should have needed to develop such a machinery, yet).

A somewhat more accessible issue that pushes the boundaries of extending our understanding of the fundamental nature of reality are so-called psi-effects, which can be defined as transfers of information of energy that are unaccounted for by our current understanding of physical, chemical or biological processes. Note that this definition does not include any positive statement about the nature of the process (e.g. it does not have to be paranormal in nature).

There are a plethora of purported psi-effects such as clairvoyance (remote viewing), psychokinesis (telekinesis), telepathy as well as precognition and premonition.

There can be no question that the general public is obsessed with these concepts. A vivid example thereof could be witnessed at the 2010 FIFA World Cup. An octopus (“Paul”) was put to the task of predicting the outcome of soccer matches at the tournament. When Paul managed to correctly predict the outcome of all of Germany’s matches in addition to the final (8 games in all – this outcome would be considered “significant” according to most of our conventions of statistical inference), a considerable media frenzy arose.

Even more puzzling – to me – is that the fans of the losing teams announced their desire to kill Paul. This makes no rational sense. Either, this is an egregious case of shooting the messenger, they think the choice undermined the confidence of their team in some kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, or they believe that Paul actually controlled (rather than predicted) the future and – as such is morally liable for the loss.

Paul (2008-2010) in action.

In any case, there is no reason to invoke paranormal effects to account for the performance at all. While I am not an expert on the color vision of octopodes, I believe that the animal had a decided preference for the color red, which could account for all observed choice data.

This public love affair with exotic (not to say paranormal) concepts is in fact understandable. Everyday experience suggests it (most primates are exquisite and hypersensitive pattern detectors). Who doesn’t have strange experiences of “synchronicity”, such as when I am called by someone who I have just been thinking about, or when a dream seems to come true later? Unfortunately, such anecdotes are of little scientific value as we do not know the correlational structure of everyday life events (e.g. a temporal correlation in daily, weekly or monthly cycles could have caused both me thinking about the person as well as make the person call me). Moreover, we usually discount statistical base rates – one usually does dream about something, and things do happen in reality. Given a large number of dreamers and dreams, it is hard to tell whether the number of “precognitive” dreams is larger than expected.

But there are scientific studies of these concepts, and I will be reviewing one of them here:

Bem, D. J. (in press) Feeling the Future: Experimental evidence for anomalous retroactive influences on cognition and affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Of course, the different psi-effects have now been studied for almost a century. For instance, in a typical study of telepathy, a “sender” views an object while a “receiver” at a separate location has to guess which object the sender is viewing. This research can be summarized and characterized by stating that while quite a few studies to report positive effects, the effect sizes are typically small, barely on the cusp of statistical significance and – as often as not – fail replication. A meta-analysis of studies on precognition suggests a small but robust psi-effect (Honorton & Ferrari, 1989). However, even a meta-analysis is not without pitfalls. It will suffer from the so-called “filedrawer effect”. Selective reporting (it is easier to publish significant rather than non-significant results) will inflate the effect in the published literature. Moreover, it is important to note that most of the history of psi-research, “real” random number generators were not available. Most algorithmically generated random numbers are only pseudorandom, in other words fully determined by a seed and usually not completely devoid of local correlations (which could produce some small effects). Finally, as much psi-research is carried out by “true believers”, neither inadvertent nor malicious influence on the experimental outcomes can be ruled out.

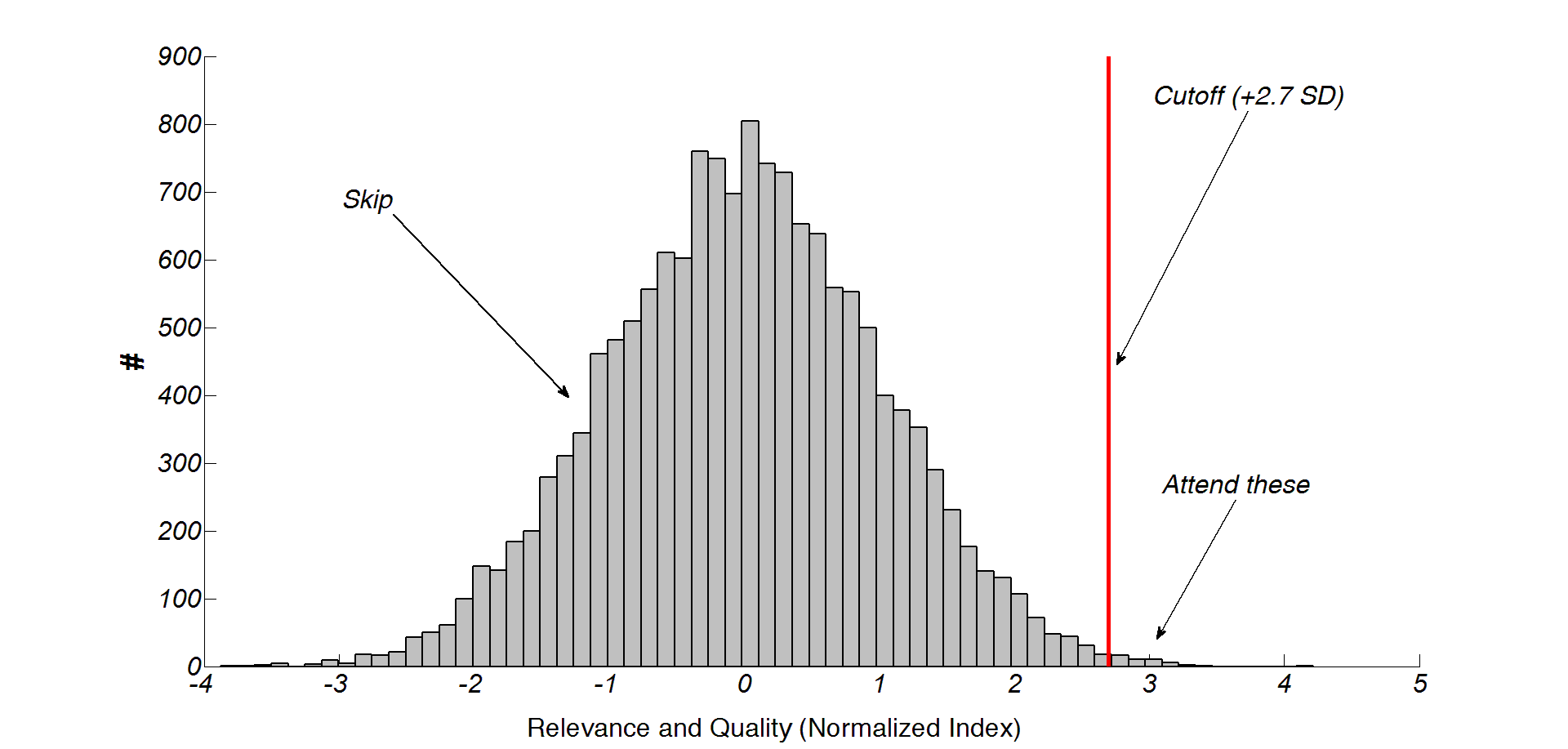

In this sense, the Bem study is likely to have a high impact. Bem is one of the heavy hitters of social psychology, has been a Cornell faculty member since 1978. The journal in which it is published (JPSP) is one of the flagship journals of APA. If you are a Personality of Social Psychologist, this is definitely one of the journals you want to publish in. Importantly, Bem is aware of all these issues stated above. To avoid issues of selective reporting and potential lack or replicatibility, he reports on no less than 9 separate experiments, each with adequate power (both in terms of participants and trials) to detect subtle effects. To avoid issues with random numbers, he uses both a hardware random number generator (the Alaneus Alea I) as well as the more conventional pseudorandom numbers. To avoid potential experimenter biases, he had the actual experiments run by a large number of undergraduate assistants.

This is important to keep in mind when considering the nature of the claim that Bem makes. The strategy in all 9 of his experiments is to take a well-established psychological effect, reverse the temporal order and see if some of the effect survives.

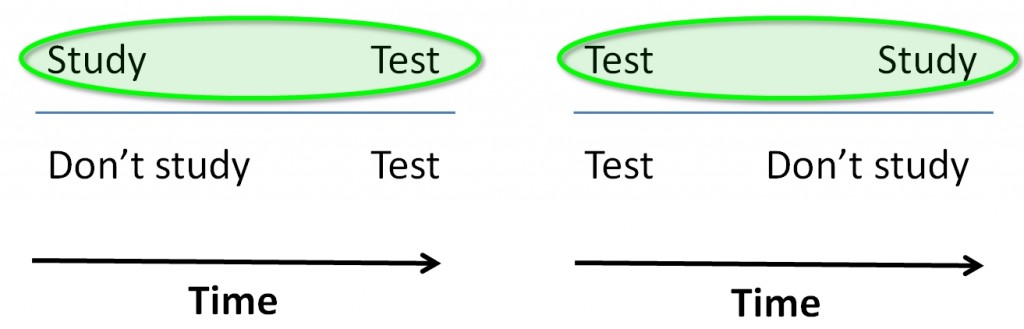

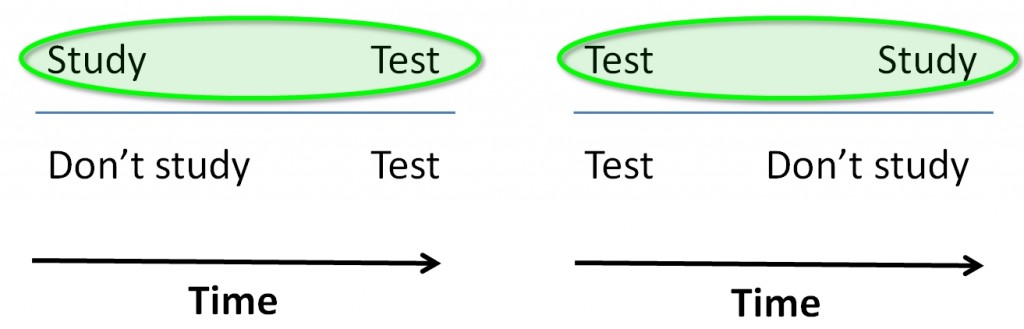

To illustrate this notion, it is best to consider a specific case (note that this is for illustration purposes only, in the Bem studies, there was no between-subjects design, in other words, all participants did the same task – it was the items/stimuli that were (randomly) put in different groups, not the subjects):

Green: The groups that do better

Let’s say we divide our participants randomly into 4 groups. One group studies while the other does not. Both are then subjected to a test. People in which group will do better? Psychological research (and common sense) suggests that it will be the participants in the group that studied. So far, so uncontroversial. However, for the remaining two groups, we give the test first, then have one group study and the other not. Which group does better now? Given our current physical understanding of the natural world (and common sense), it should not matter. Why? Because the test precedes the studying. The cause has to precede the effect. If not, there have to be some kind of retrocausal (backwards in time) effects going on.

This is – as outrageous as it sounds – in a nutshell the logic and claim of the Bem study. Is the claim so outrageous that we can dismiss it out of hand? I’m afraid not. As skeptical as I am obliged to be as a scientist (one could say that my a priori willingness to believe this is very, very low), it is important to keep an open mind. History abounds with cases where an “outlandish” (for the time) concept was wholly rejected by the scientific establishment of the time, but which has since become the mainstream position. The theory of plate tectonics is a case in point. Alfred Wegener noted the fit of the landmass-shapes (particularly Africa and South-America) and suggested continental drift. It took about 50 years for this theory to be somewhat accepted by geologists. Similarly, Semmelweis suggested that childbed fever is caused by germs and can be prevented by simple hygiene. Despite dramatic successes in reducing childbed fever in his own hospital ward after introducing mandatory handwashing by surgeons, the reception of his ideas by the medical community of the day was rather unkind. While the details are somewhat murky, it seems that he was actually committed to an insane asylum by his colleagues (he died shortly thereafter, beaten to death by some asylum guards).

Not every lunatic is a Galileo, but these examples (among many others) should serve us as cautionary tales. We really have to consider the empirical evidence to make a judgment.

Bem reports a total of 9 experiments in his paper. They fall into 4 broad categories, each leveraging a well understood (or at least well studied) psychological effect: Approach and avoidance of positive and negative stimuli, Priming, Habituation and Memory. There is more than one experiment per category because Bem varies stimulus material, nature of the random number generator, number of trials and participants and so on. Within each experiment, he tries different ways of analyzing the data (e.g. parametric vs. non-parametric tests), different ways of data pruning (different criteria for outliers) and different ways of transforming the raw data (e.g. log transforms). Broadly speaking, none of this mattered. The results were robust both in regards to different ways of analyzing the data as well as different ways to elicit them – the effect sizes are quite consistent across experiments.

The general paradigm (varied in details depending on the specific experiment) consisted of the participant having to make a forced choice between two similar alternatives. All experiments were run on a computer. After the participant made their choice, the computer would then determine the level of the independent variable. For instance, for the approach/avoidance condition, the participant would be asked to check one of two (virtual) curtains, one of which hides an image. All images were taken from the (standardized) IAPS image database, so the valence (and evoked arousal) of a given image for an average participant was known. After the choice of the curtain, the computer determined what kind of image to place and where to place it. Psychological theory suggests that people tend to seek out positive stimuli and try to avoid negative stimuli. If they are able to do this before they even see the stimulus (the curtains look identical at the time of the choice), it could suggest the operation of retrocausal processing.

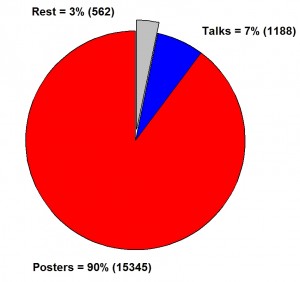

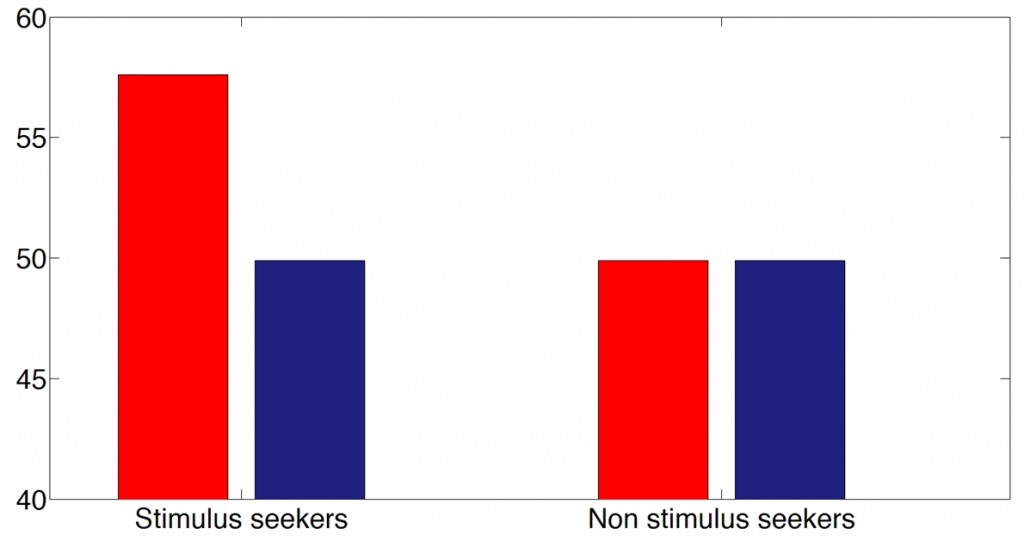

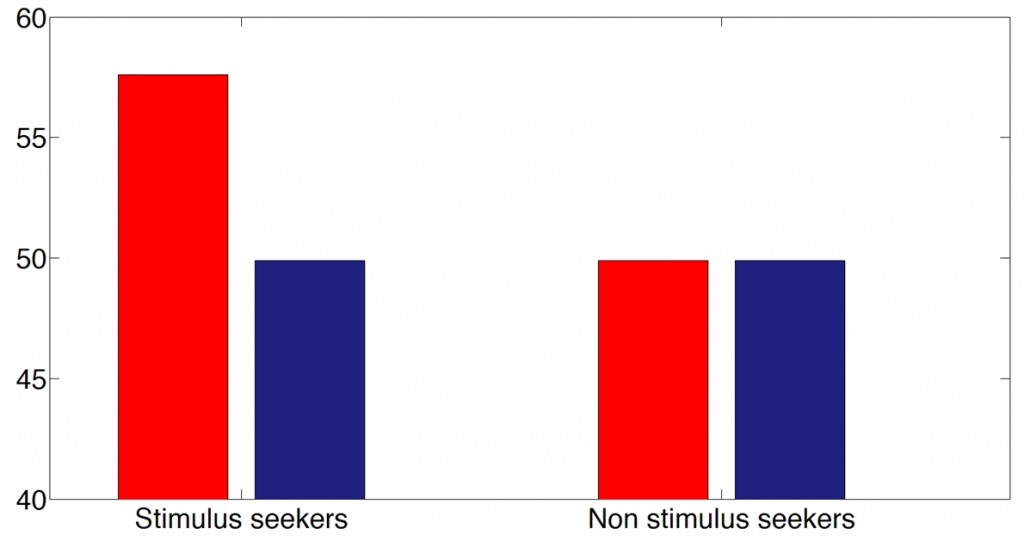

Lo and behold, that is what Bem reports. People can do this. The effect sizes are not huge, but they are able to do it consistently and significantly. In Experiment 1, they are able to detect the positive image (erotic images, actually) 53.1% of the time. Small (expected would be 50%), but significant (p=0.01). Interestingly, participants were also queried about their stimulus seeking behavior. Previous research had suggested that Extraversion correlates with stronger psi effects. When dividing his participants into different groups -split by stimulus seeking trait strength – the effect seems to be carried entirely by the stimulus seekers. The correlation between stimulus seeking and psi effect in this Experiment was 0.18 (p = 0.035). The Bem paper contains no actual figures, so I took the liberty to make one, summarizing experiment 1:

Hit rates for erotic (red) and non-erotic (blue) images

The experiments on priming yielded similar results. As is well known, reaction times to a positive (e.g. beautiful) image will be delayed if a incongruent word (e.g. ugly) is (subliminally) presented just beforehand. Bem shows a sizable (and highly significant) priming advantage of congruent over incongruent primes of 27.4 ms. The surprising thing is that he reports that the “prime” (not sure if that is still the right word) can be retroactive. If the prime was presented after the image, there is still an advantage of 16.5 ms in favor of congruent “primes”, which was reported to be highly significant.

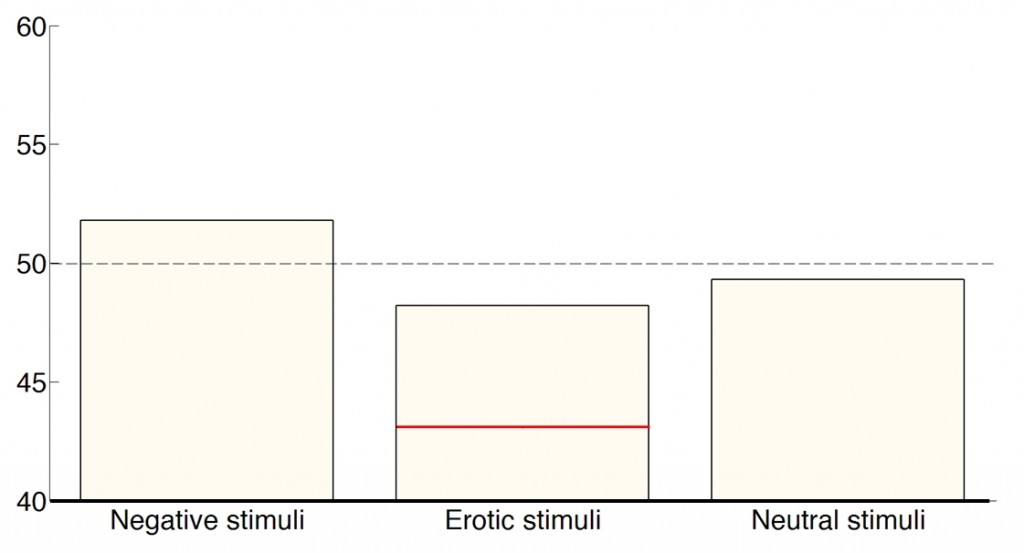

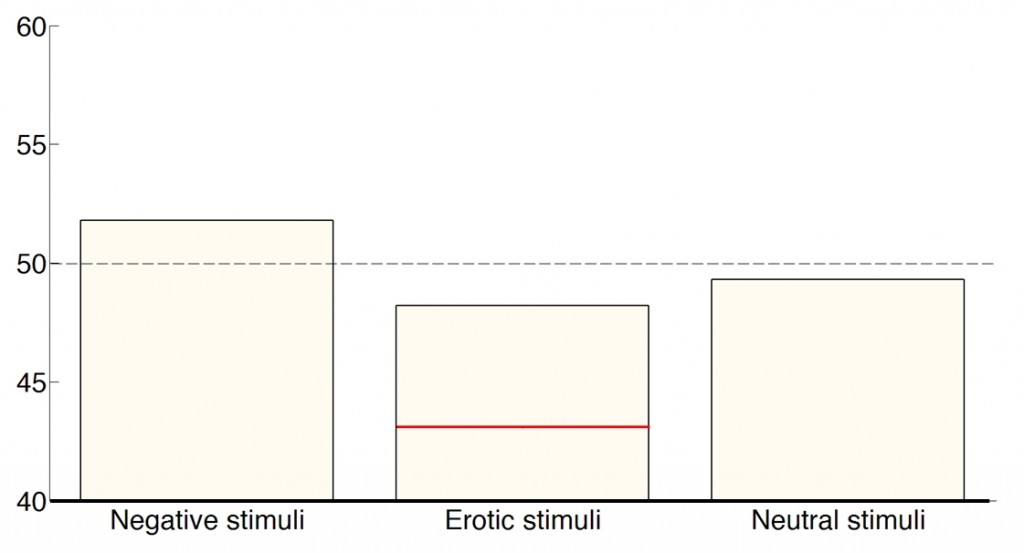

The experiments on habituation utilize the well known effect that the valence of an object changes with repeated (subliminal) exposure. Initially positive things are experienced as less positive with repeated exposure, initially negative things are experienced as less negative with repeated exposure. So far, so good. However, in Bem’s experiments, the habituation happens after participants picked an image and should thus have no effect. But it does. Or so Bem reports. Again, here is one of the figures I created based on the table in the paper, for Experiment 6:

Percentage picked. Horizontal red line: Percentage picked by those scoring high on erotic stimulus seeking

Again, the effects are subtle, but significant (no CIs are reported, so I am not plotting them). The group high in erotic stimulus seeking exhibits the effect much more strongly. If there was no effect, all 3 bars should be close to 50 (as the one for the neutral stimuli is).

Finally, Bem reports two experiments on recall, in which participants had to memorize a list of words (nouns, from 4 categories), and were later familiarized with a randomly picked subset of the words. Lo and behold, participants did better on words in the subset that was practiced on later compared to words that were not. The effect is small: 2.27%, but significant. Also, high stimulus seekers do exhibit it much more strongly: 6.46%.

That’s it regarding the empirical evidence. Bem is largely agnostic regarding the physical or neural mechanisms underlying these effects. He does suggest – invoking Bell’s theorem – that universe of non-locality and entangled particles is not necessarily inconsistent with these effects.

So far Bem. But what on earth are we supposed to make of this?

Both the experimental procedure as well as the statistical analysis is so straightforward that there is very little hiding room for potential bugbears. The results were robust to all kinds of little variations and checks that I chose to omit here (such as congruent response biases of the random number generators). Given that he reports evidence from 9 studies, there is little chance of a file drawer problem.

So this leaves me in somewhat of a conundrum. As a scientist, I set out to crucify Bem on his claims. Now, I am almost compelled to say: “I can find no fault in this man.”.

But seriously, while the evidence seems to be compelling, there are some remaining questions. First and foremost, I wonder why the effects are so small and fleeting if they are so consistent. While this is typical for psi-studies, there must be a way to boost the signal strength if the effect is real. I am surely not alone when I say that I am somewhat uncomfortable with phenomena that perpetually hover around the threshold of statistical detectability. Moreover, it would have been very interesting to see if the same individuals exhibit these abilities in more than one task. The paper does not mention anything about this, but presumably new participants were recruited for each experiment. If it is a personal trait, some should show it more than others (as was indeed demonstrated with the stimulus seekers), but individuals should show it across tasks, consistently and reliably.

The most bothersome worry is that we are dealing with some kind of laboratory-induced phenomenon. Ironically, I would expect to see measurable real-life effects, if real. For instance, I wonder whether casinos do less well than expected by probability theory alone. To my knowledge, this is not the case, but I do not know much about casinos. If psi-effects are real, those high in psi should be able to beat the house at least to some degree. Also, no one else seems to leverage these effects, suggesting that they might not be real after all.

I think at this point, the most prudent course of action is to call for large scale replication before going any further with a theoretical interpretation of these effects.

On a sidenote, the research on psi provides a cautionary tale on our interpretation of subtle effects in psychology or neuroscience in general. We encounter those quite frequently. Extraordinary claims (such as those advanced by Bem) do require extraordinary evidence. But what about more ordinary claims? What kind of evidence do we accept for those?

Edit: Here is a summary of the rationale in a nutshell. If these results are real (a big IF), how else could one explain these consistent findings (e.g. that studying AFTER a test will make one better while taking it? If that is true, precognition seems parsimonious). It challenges the cause/effect relationship, our understanding of temporal order in the universe, etc.

Given our understanding of causality, anything that you do AFTER the fact should have no influence on the outcome whatsoever. But (according to Bem), it does. In 9 different experiments. So what is going on? Short of intentional or unintentional research misconduct, nothing comes to mind. This – however – is unlikely, given the stature and career stage (emeritus) of someone like Bem. Data collection responsibility was spread across a large team of undergraduates, which makes it less likely that potential issues originate there, either. Of course, the overall effect is small, so it might be interesting to reanalyze the data by who collected them – which is probably not feasible, due to the small n. Also, it is unclear from the report how independent (or correlated) the efforts of the undergraduate research team were (e.g. did one of them write the software, one of them all the recruiting, one of them all the collecting, etc.). The higher this between-experimenter correlation, the more likely that a single mistake somewhere will propagate. That is why an independent replication is imperative. A dose-response relationship (e.g. the effect declines as the future events are more distant in time) would also increase my confidence in this.

The experiments themselves are very straightforward. There are some details that need to be considered (e.g. the time course of the retroactive priming experiments are not an exact mirror image of the forward priming experiments, but there is a good reason for that, and it shouldn’t matter anyway, what happens AFTER the judgment), but nothing interpretation-altering. The statistics seem to be sound as well. I believe that is ultimately why an august journal like JPSP was forced to publish this. The data itself is compelling, as are the experimental designs. If the report is accurate (and reflects what happened during the experiment), they effectively had no choice but to publish it. Might be interesting to see the reviews, which surely pointed this out…

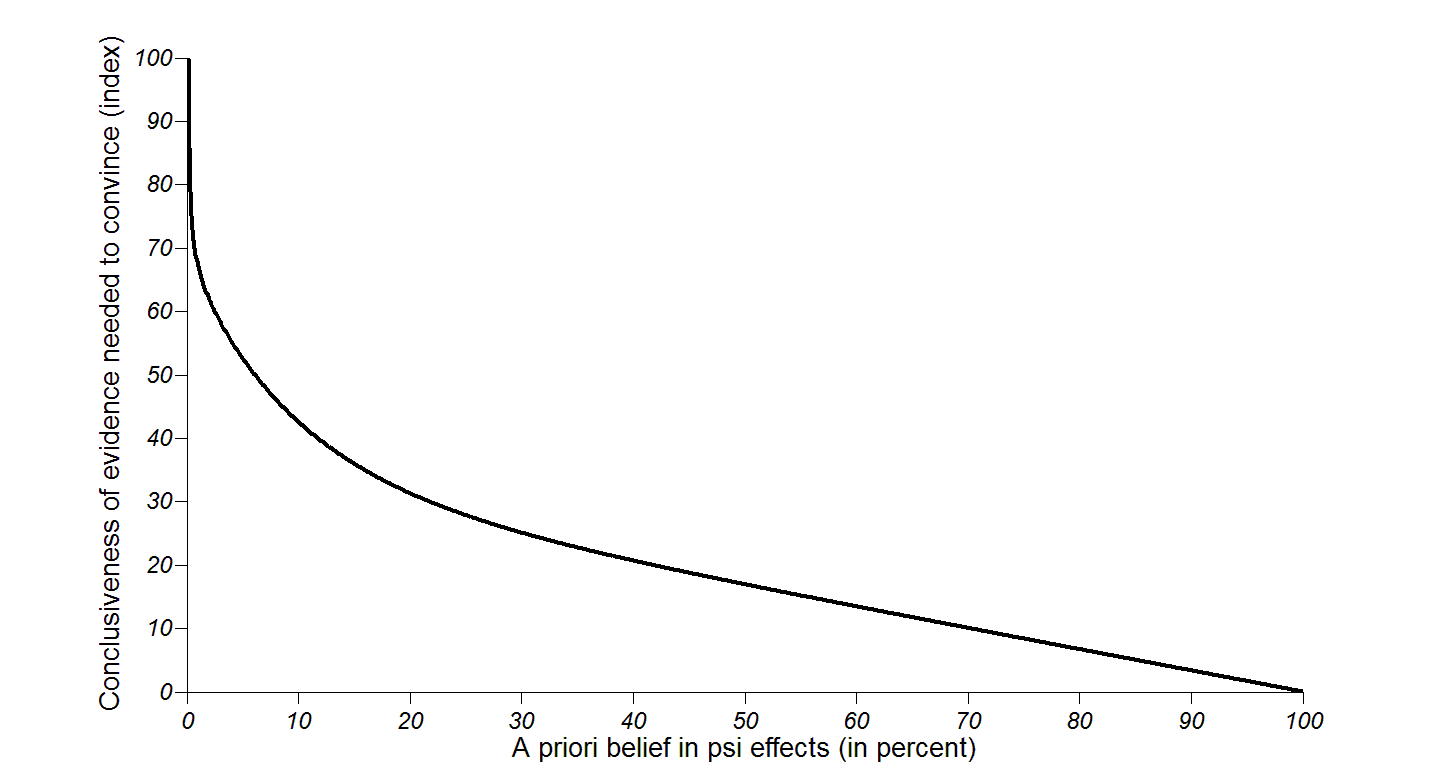

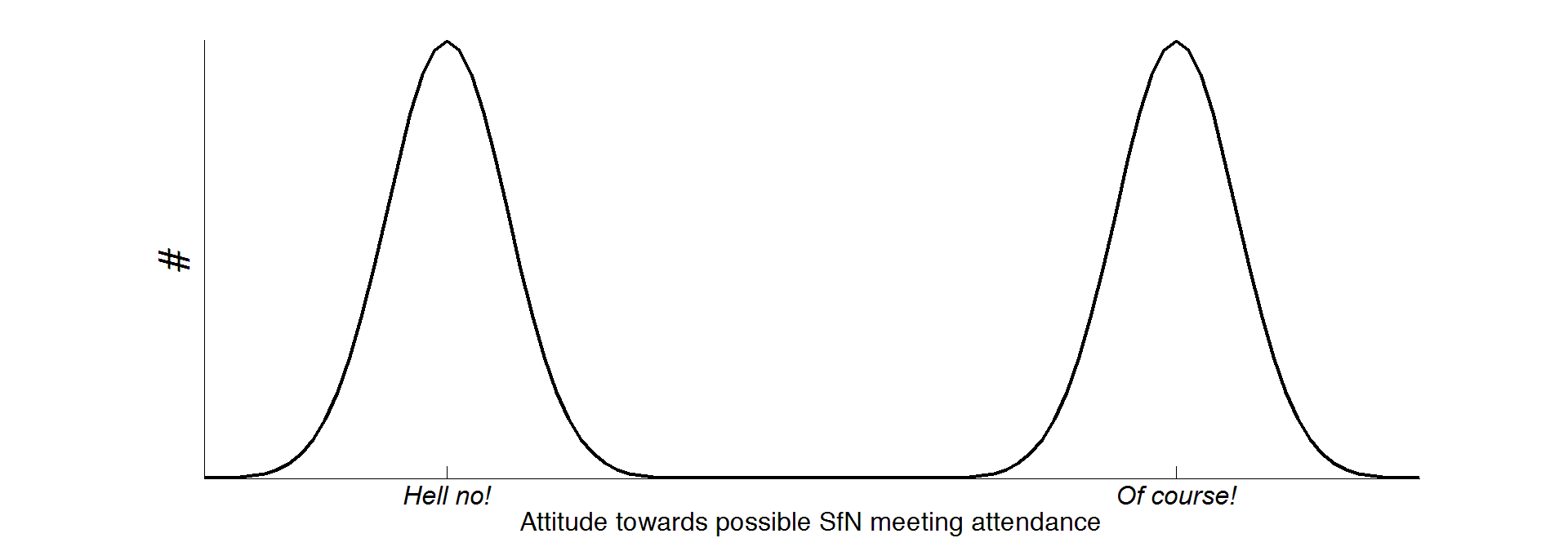

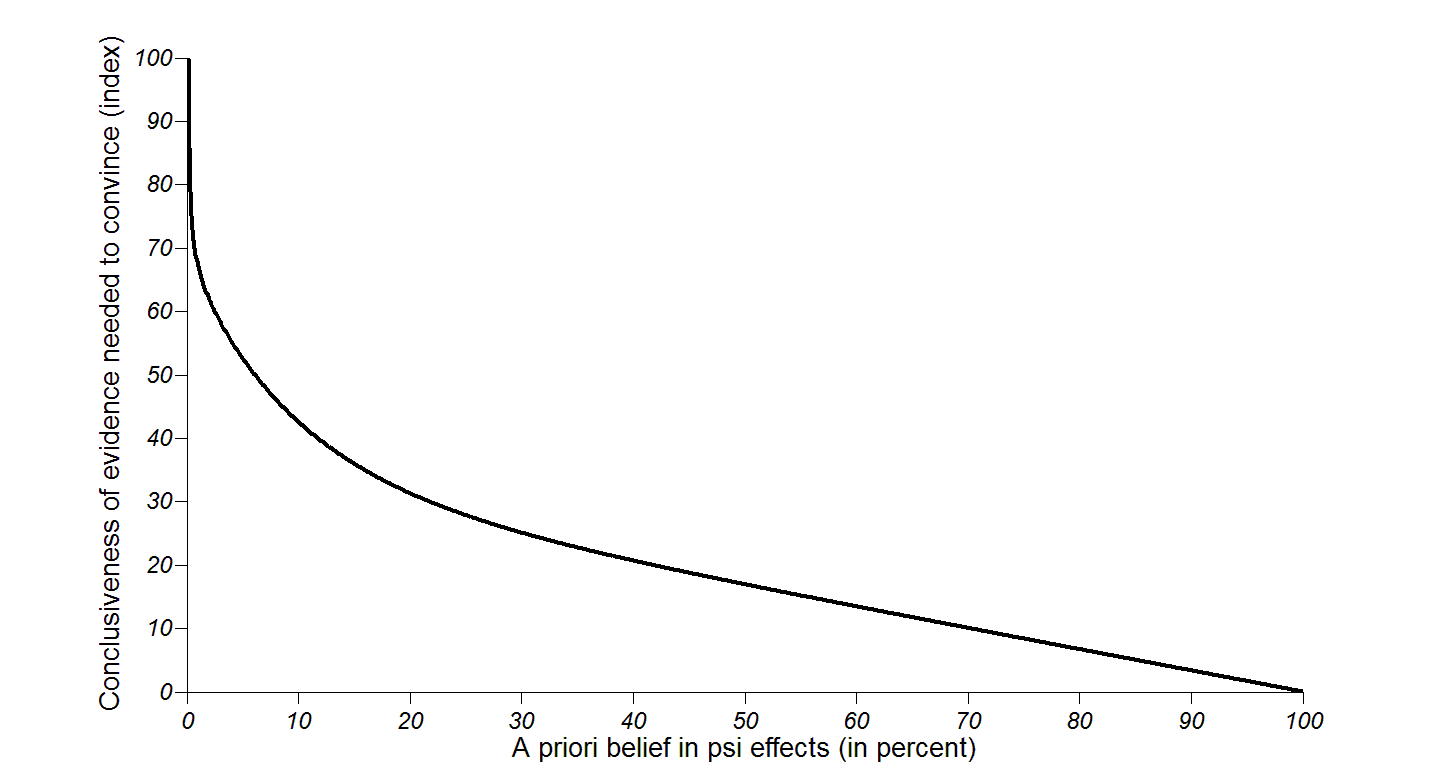

On a side-note, after speaking to quite a few of my colleagues about this, I realize that the willingness to take these results seriously – as opposed to dismissing them out of hand – is a function (not sure which one) of the PRIOR probability that such effects exist. If this is true for science in general (it is true for people in general – both in terms of what people are willing to accept in faulty logic as well as faulty evidence, if it supports their position, but the reference escapes me), then we are in big trouble. The data is the data. That is all we have to go by (that and the way they were collected) and how they connect to the claims. In this case, everything seems to be consistent. The only way I can account for the bias is to assume a low initial probability (believe in) psi-effects, about as follows:

In other words, no data whatsoever (quantity and quality) could convince the complete sceptic (0% prior probability) while the complete believer (100% prior probability) needs no data at all. This has the feel of truth, but as pointed out above, we are all in deep trouble if this is true. Let us be scientists about this. I would like to determine the shape of this distribution empirically. So please help me, it will take only one minute of your time. Survey

At the same time, this *is* a haunting result, so perhaps the extra scrutiny is warranted.

Edit 2: This is getting longer and longer (too long), but the controversy continues, so I want to make some additional points:

a) It is important to keep an open mind, particularly as a scientist. When Galileo begged his detractors to look through his telescope to see the sunspots for themselves, they refused. Their argument: How can we know that the devil isn’t in the machine itself and is intentionally misleading us?

b) It is not per se a problem that Bem does not outline a potential mechanism. The discovery of effects typically precedes the explanation (uncovering a mechanism) by decades, centuries or even millenia. Case in point: Radioactive effects. To say nothing of electricity or magnetism. Static electrical effects were known to the ancients. But not their mechanism.

c) The fact that the effects themselves are small is irksome, but not in itself reason enough for dismissal. Effect sizes in psychology are typically notoriously low. Even in neuroscience, one can have small effects. Take choice probabilities for example. They are usually reported in the range of 0.52 to 0.55 (with 0.5 being the chance value). What matters is how reliable the effect is and how unlikely it is gotten by chance (the p value). In the Bem case, the cumulative p is staggeringly low. As a matter of fact, I would expect the effects to be subtle. If they were strong, there would be no controversy whether psi-effects exist. It would be obvious.

d) To restate the premise: They can’t test a specific hypothesis, because the existence of an effect (the explanandum) is itself in question. They do – however – test a general (null)-hypothesis to establish the effect. That (null)-hypothesis is that common sense and our current understanding of the physical world suggests that *nothing* that happens *after* the choice point should affect the choice itself. They find that it – statistically speaking – does matter quite a bit what happens afterwards and they reject the null hypothesis. Establishing the existence of an effect. This is done all the time in science, and in psychology in particular. They conclude that we are dealing with a psi-effect, because that is how psi is defined (an effect which is (currently) unexplained by our understanding of biological or physical processes, see the definition above).

Postscript

Three things became really apparent during this episode:

1. A single study is not compelling enough to overturn beliefs if they are dearly held.

2. Media attention and excitement should be withheld until there is an independent replication. Attempts at replication should be incentivized, as they don’t happen nearly enough (unless there is a spectacular case, like this one).

3. People were bugged by the result, not the methodology. As a matter of fact, the experimental approach (with several substudies) would have passed muster in most fields, including psychology without a second thought if the results had been more in line with expectations. No one would have batted an eye, no one would have attempted a replication. This should give those with a concern for the state of the field pause for thought. How many results that are wrong do we believe because we expect them to be true? On a side note, providing expected results is the favorite strategy of serial cheaters, only the sloppiest and most egregious of which eventually get caught. #likelyiceberg

We need more replication attempts. not just in celebrity cases like this.