We are upon the 100 year anniversary of the start of the 1st world war. Most people alive today don’t fully appreciate the cataclysmic forces that were unleashed in this conflict, several of which still shape world events today. Of course, most people are aware of the sequel, World War 2 – a very different, yet closely related conflict. More subtly, WW1 brought on the rise of communism (seeding the cold war) as well as the demise of the Ottoman empire. The way in which weak and inherently unstable nation states like Syria or Iraq were carved out of the corpse of the Ottoman empire troubles the world today. As was revealed by removing the strongmen in the early 2000s, most of these states could only be stabilized and pacified by dictatorships. Which is not a problem per se, unless one has a psychopathic and expansionistic one in charge of a major regional power (such as Iraq), in a region that decides the energetic fate of the world economy, as the experience of the 1970s illustrated. Put differently, Iraq really was about resources, but in a more subtle way than most people believe.

But why have a conflict so apocalyptic in the first place, as cataclysmic as it was? Briefly, because everyone wanted to fight, no matter how senseless it was in economic terms. The sequel – WW2 – could happen only because no one (except for Hitler) wanted to or could afford to (given the debt accumulated in WW1) fight.

A great deal can – and has been – said about what amounts to the suicide of the West, as it was classically conceived. Briefly, I want to emphasize a few points.

*Really everyone in Europe wanted to fight, including Germany (who felt itself surrounded by enemies), Russia (who wanted to come to the aid of their Serbian friends), Serbia who felt its honor wounded by the Austro-Hungarian empire, Austria-Hungry who wanted to teach the Serbs a lesson and get revenge, France who was in a revanchist mood since 1871 and saw the population development east of the Rhine with great concern, England who felt its imperial primacy threatened by an upstart Germany and even Belgium, who was asked by Germany to stand down so that Germany can implement the Schlieffen plan but instead blocked every road and blew up every bridge they could.

*The irony of the Schlieffen plan: Germany saw itself surrounded by powerful enemies (France and Russia). The way to beat a spatial encirclement is to introduce the concept of time – the Russians were expected to mobilize their armies slowly. This gave the Germans a narrow time window for a decisive blow against Paris to knock out France in time before turning around and dealing with Russia. In addition, this time pressure is so severe that while Germany had the necessary artillery to knock out the French border forts, it did not have the time to do so. This necessitated going through neutral Belgium, which brought he British and – eventually – the US into the war against Germany. The irony is that this worry about the Russians was misplaced. As a matter of fact, the Russians showed up way earlier than anyone expected and started to invade East Prussia, in an attempt to march on Berlin. However, while they were early, they were also a disaster. A single German army defending East Prussia managed to utterly destroy both invading Russian armies – and then some. Given this outcome, there was no need for the highly risky Schlieffen plan.

*The irony of having a war plan in the first place. But this is only obviously a problem in hindsight as well. In WW1, both sides made disastrous mistakes on a regular basis. As a matter of fact, the rate of learning was in itself appallingly slow – infantry operated with outdated tactics and without helmets well into the war. Ultimately, the side that was faster at improvising and made the lesser amount of disastrous mistakes won.

*The irony of constructing a high seas fleet for Germany. This got the English into the conflict, which turned it from a small regional engagement to a world war. Immensely costly to build, this fleet did the Germans a world of good, sitting in port for the entire duration of the war (with the exception of a brief and inconclusive engagement in 1916) and providing the seed for revolution in 1918, bringing the entire government down.

*The difference in conflict between WW1 and WW2. As mentioned above, everyone wanted to fight in WW1. Consequently, well over a million people were dead within a few months, whereas it took almost two years for WW2 to get “hot”.

*It is a legitimate question to wonder what would have happened if the US hadn’t intervened in 1917. Without US intervention, there probably wouldn’t have been enough strength remaining for either side to conclusively claim victory (Operation Michael in 1918 would probably not have been successful regardless and without US encouragement, the allied offense would likely have suffered the same fate as the one in previous years). But the war couldn’t conceivably go on any longer regardless, due to a global flu epidemic and war weariness on all sides. What would the world look like today if the war had ended in an acknowledged stalemate, a total draw?

*Eternal glory might be worth fighting for, but the time constant of glory in real life is much shorter. Most people have absolutely no idea what different sides were fighting for specifically, or be hard pressed to even name a single particular engagement.

*Much has been made of the remarkable coincidence involving the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand. It is true that the assassin struck his mark only after a series of unlikely events, e.g. Ferdinand’s driver getting lost, and the car trying to reverse – and stall – at the precise moment that the assassin Princip is exiting a deli (Schiller’s Delicatessen) where he got a sandwich. Given the significance of subsequent outcomes, one is hard pressed not to see the hand of fate in all of this. However, there might be a massive multiple comparisons problem here. First of all, Princip was not the only assassin. To play it safe, six assassins were sent and indeed, the first attempt did fail. More importantly, this event was the trigger – the spark that set the world ablaze – but not the cause. Franz Ferdinand makes an unlikely casus belli. Not only was he suspected of harboring tendencies supporting tolerance and imperial reform, Ferdinand had married someone who was ineligible to enter such a marriage. This was a constant source of scandal in the Austrian-Hungarian empire. The marriage was morganatic in nature, his wife was not generally allowed to appear in public with him and even the funeral was used to snub her. Therefore, the emperor considered the assassination “a relief from great worry“. More importantly, it can be argued that this event is just one in a long series, all of which could have lead to war. Bismarck correctly remarked in the late 19th century that “some damn thing in the Balkans” will bring about the next European war. Indeed, the Balkans was the scene of constant crises going back to 1874 and including 1912 and 1913, all of which could have led to a general war. If anything, it can be argued that fate striking in 1888 was more material to the ultimate outcome. In 1888, Frederick III, a wise and progressive emperor died from cancer of the larynx, after having reigned for only 99 days. This made way for the much more insecure and belligerent Wilhelm II.

*What remains is the scariness of people ready to go to war even though it makes absolutely no economic sense. In a hyperconnected world of globalized trade that closely resembles our own (mutatis mutandis, e.g. the US stands in for the British Empire as the global hegemon). In addition, there was a full – ultimately wasted – month for negotiations between the assassination of archduke Ferdinand and the beginning of hostilities. This raises the prospect of a repeat. At least, it doesn’t rule it out. In 1913, there had been an almost 100 year “refractory period” (respite from truly serious, all-out war) after the Napoleonic wars as well. However, odds are that if it should happen again, repeating the 20th century in the 21st, it will happen in Asia. Asia has the necessary population density and a lot of its key countries – China, Japan, Russia, South Korea, India and Pakistan – are toying with extreme nationalism. As the history of the 20th century illustrates, that is a dangerous game to play.

Ideology poisons everything, as it rotates perceptions of reality

It is obvious where ideology comes from. It solves a lot of problems. A small tribe needs to agree on a distinct course of coherent action. Otherwise, its strength is frittered away, defeating the very point of finding strength in numbers, i.e. of being a tribe in the first place. Ideology also solves a lot of freerider and principal agent problems in general. It makes individuals do things for the common good that objectively impedes their subjective welfare and that they wouldn’t otherwise do. This also makes good sense along other lines. Small tribes perish or flourish as a whole (a genetically highly interrelated group), not as individuals. Ideology promotes fitness on the level that it matters, the group-selection level.

However, we no longer live in a world of small, competing, ever warring and highly xenophobic tribes. On the contrary, we live in an extremely large society, in terms of the US about 2-3 million times as large as the typical tribe, which constitutes the form of social organization that was the norm throughout almost all of human evolution (if one considers the whole world as one big globalized and highly interconnected society, it is about 70 million times as large). So the archaic model of social organization clearly doesn’t scale. Yet, its roots are still with us. For a simple test, try watching a soccer game (or indeed any team sport) without rooting for a particular team (or watch a game where you don’t care about any of the teams). The athletic display won’t be any different, but it will likely be rather un-riveting.

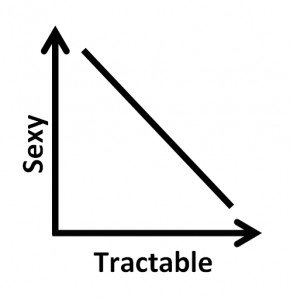

So in modern times, tribalism is a cancer that is threatening to tear society apart. Why? Because most of the remaining societal problems are extremely thorny and complicated (that’s why they remain in the first place – we already addressed the easy ones). They usually don’t lend themselves to resolution by experimental approaches. But a lot typically rides on the outcome, the answer to these questions. This gives ideology a perfect opening to take root. For instance, modeling the climate is extremely complicated. All models rely on plenty of assumptions, relatively sparse data and are so complex that they are even hard to debug (or to know when debugging was successful). It is very hard for anyone to ascertain what is going on, let alone will be happening in the future, yet ideologists are very keen to either dismiss any probability of warming or assume dramatic human-caused warming as a certainty. The confidence of both camps far exceeds the data cover. Where does it come from? Potential holes in the story are simply filled in by ideology. Similar questions arise – for instance – in history. A key question is history is: What makes a society successful? The most realistic answer is that it likely involves a complex interplay of geography, genetics and culture. It is extremely hard to assign relative weights to these factors, as it is impossible to do experiments on this issue. Yet, one can make a good living writing books asserting that it is all geography (implicitly or explicitly assigning a factor of zero to the other factors), all culture or – recently – by pointing out that the weight of the genetic factor is unlikely to be zero, unfashionable as it might be, given the political climate.

Which position is most compelling to you says much less about which position is true – at this point, the evidence is far from conclusive – but much more about you: Which position do you want to be true? Why would you want a particular position to be true? Because it neatly fits in with your worldview or Weltanschauung.

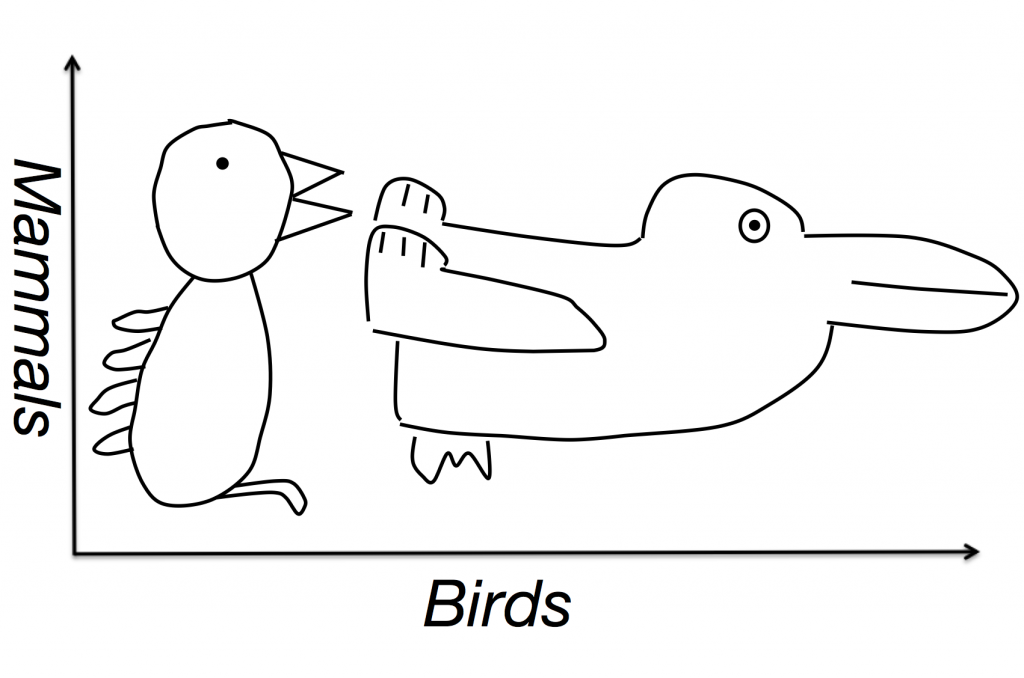

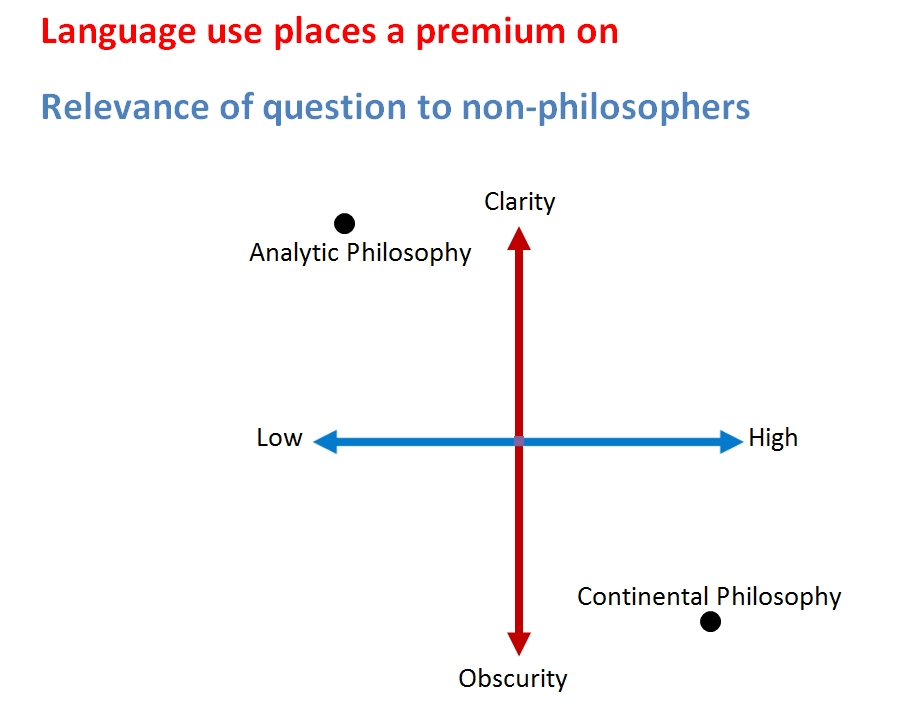

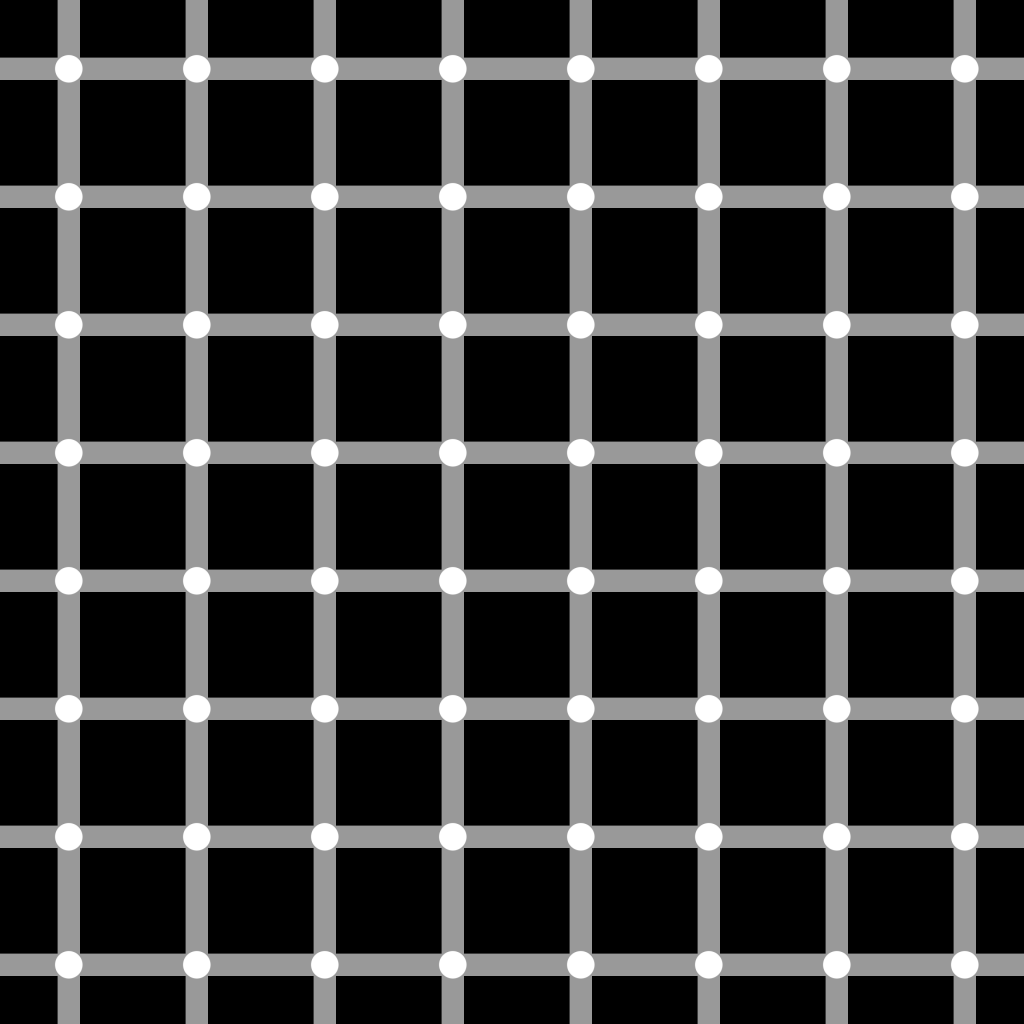

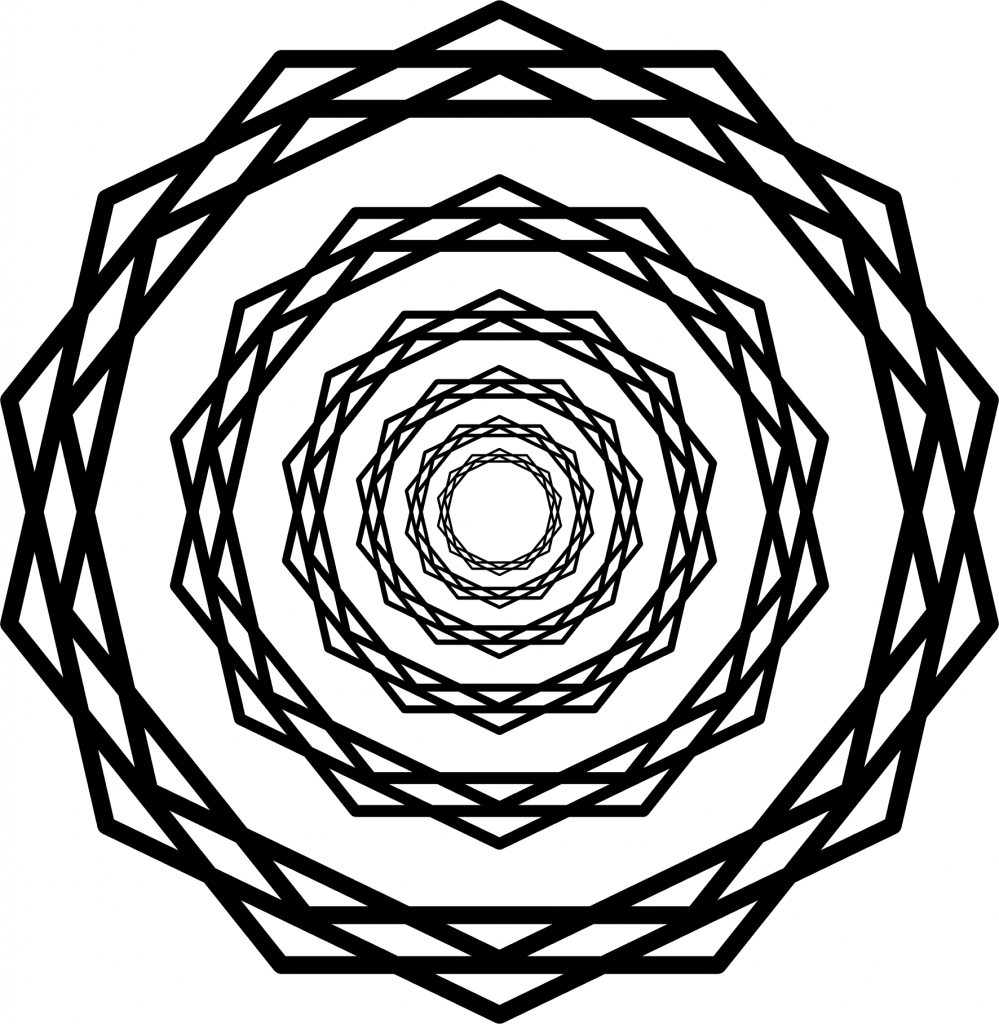

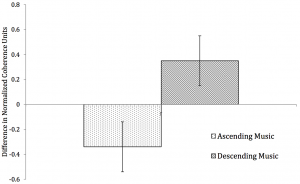

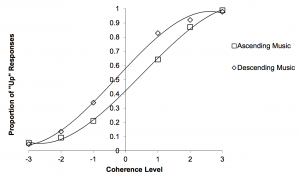

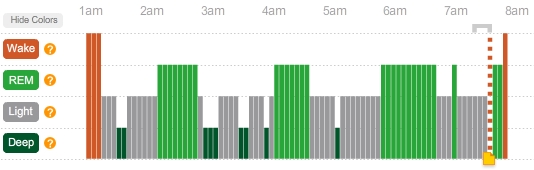

What is the problem with that? The problem is that people on the two different ideological poles simply look at the same data from two different vantage points (e.g. left vs. right, see figure 1).

Figure 1: This represents reality. Two ideological camps have positions on issues that vary along the left/right dimension. Some of them are more valid than others, but no camp has a monopoly on validity, given these issues.

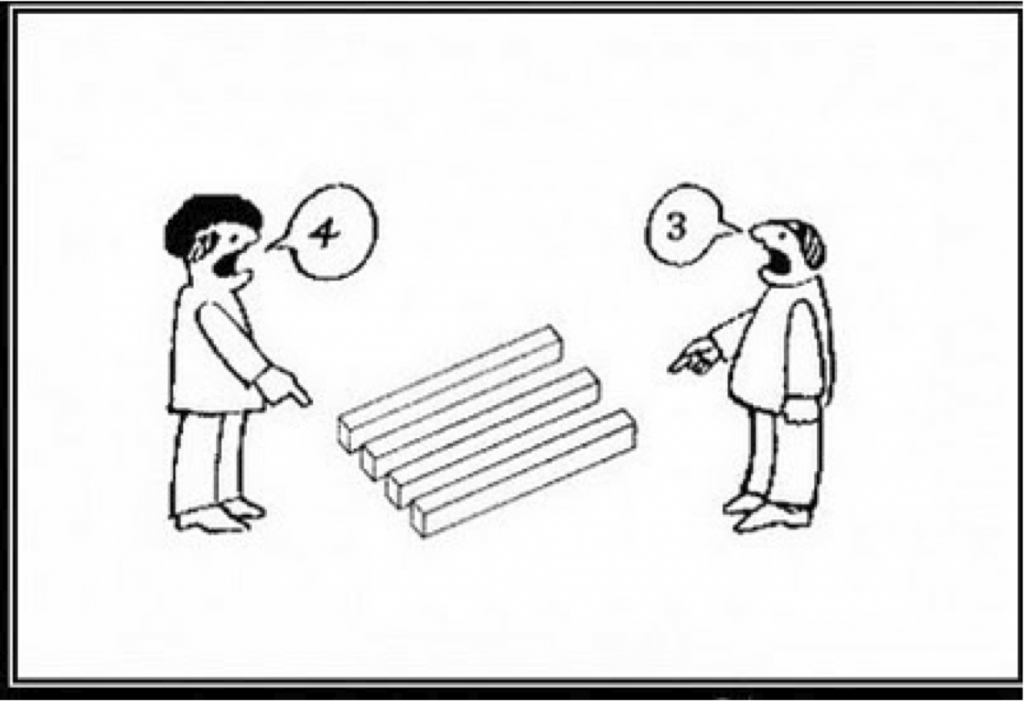

But in the mind of the ideologue, any issue doesn’t come down to a horizontal difference, but rather a vertical one – the ideologue assumes that the positions in one’s camp are valid, the others invalid. But when one sincerely perceives a difference in appraisal as a difference in fact (where one is either right or wrong), resolving these issues is basically impossible.

Figure 2: Liberal ideology. From the liberal perspective – which corresponds to a clockwise rotation of reality by 90 degrees – their positions are now perfectly centered in ideological terms. They just happen to be right, whereas the other camp is just wrong about everything.

Figure 3: Conservative ideology. From the conservative perspective – which corresponds to a counterclockwise rotation of reality by 90 degrees – their positions are now perfectly centered in ideological terms. They just happen to be right, whereas the other camp is just wrong about everything.

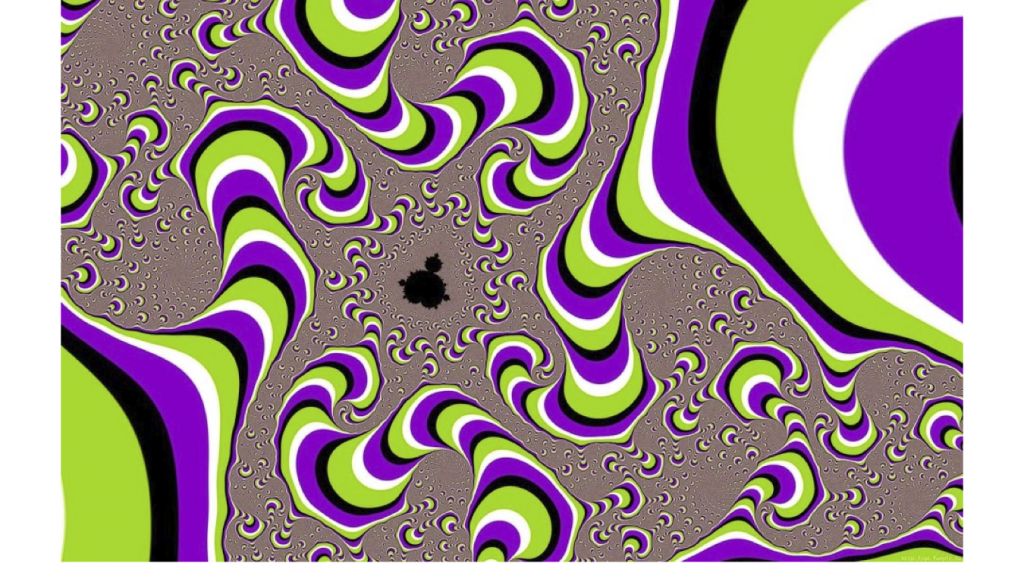

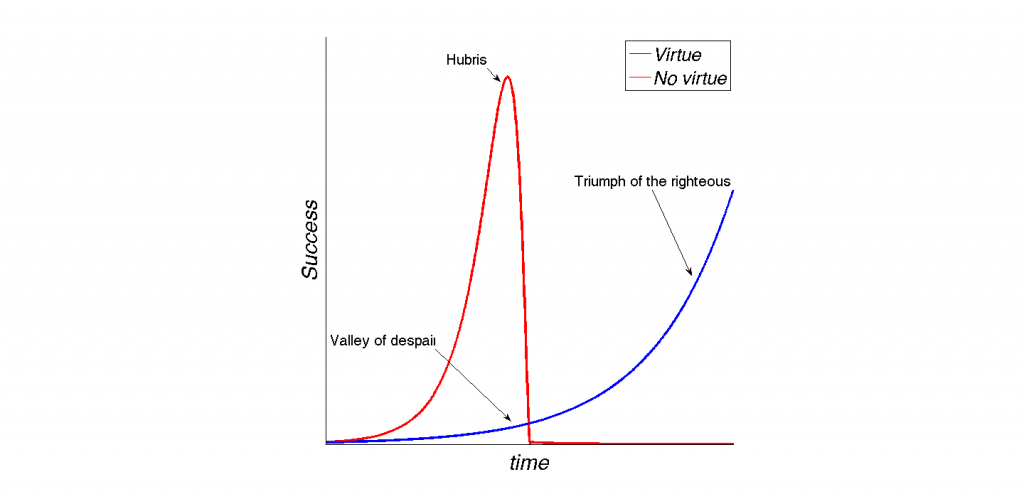

The insidious thing is that this happens inadvertently and automatically. People that take a particular position will naturally see the other one as invalid and just plain wrong. Not as a difference in position, but as a matter of (moral) right and wrong. Righteousness vs. wickedness. Feeling this with every fiber of their being, leads to an immediate dismissal of the other position. If they can see the truth so clearly, why can’t the other side? Surely, they must be willfully ignorant, malicious or both. Ascribing turpitude usually follows. Worse, this destroys any reasoned discourse. Making a nuanced argument will go unappreciated, as the ideologue will not understand its nuance. Instead, it is automatically transformed into a low dimensional ideological space, perpetuating the framework of divisive tribalism, with all of its odious consequences. As we’ve known for a long time, it is basically impossible to convince someone with complete certainty that they are wrong, regardless of how ludicrous their position is or how much it flies in the face of new incoming information.

It is awfully convenient that the same people who disagree with us are also those who are dead wrong about everything. If the issue is important enough, (religious) long and brutal wars have been fought about this.

The problem is not to be wrong about something. That happens all the time. The problem is how right it can feel to be so wrong. If you want to experience this for yourself, there is a simulacrum with a somewhat juvenile name that deals with issues like information accumulation, cue validity, confidence and uncertainty. It allows an apt simulation of what social primates can be absolutely convinced of, even in the near absence of valid information. This can be rather scary. An important difference to reality is that in reality, there is rarely a reality check (feedback from reality or god) whether one’s beliefs actually correspond to the truth.

What is the way out of this? Acknowledging that this is going on. Metacognition allows for a possible avenue of transcending these biases. Naturally, this will take a lot of training, particularly as most actors (the media, for instance, have every incentive to be as divisive as possible in their rendering of events). But by appreciating the complexity of problems and by embracing the fundamental uncertainty inherent to life, one opens the possibility that this can be done. It won’t be easy, but there is no real alternative. A de facto perpetual cold civil war is no real alternative. Certainly not a good one.

The problem with the ideologue is that they are constitutionally unable to learn from feedback. As they already see themselves as right to begin with, the error is irreducible. As such, they are the natural enemy of the scientist. In particular, it is important not to give people a pass for being uncivil (and not helpful) just because they agree with us ideologically.

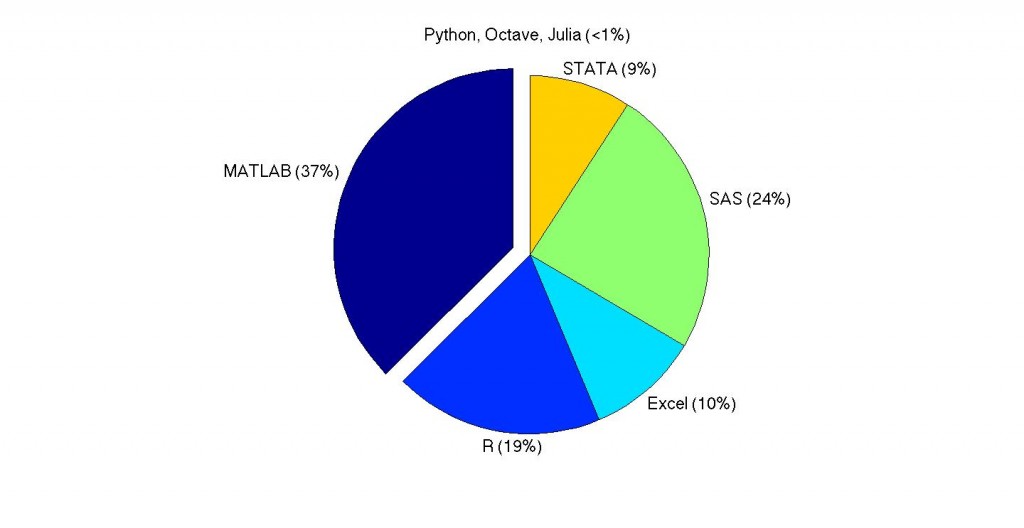

Tribalism had its day, for most of human history. And it was very adaptive. But today, it no longer is. Instead, it is needlessly divisive. Is it really useful to judge people based on what browser or operating system they use, what car they drive, what phone they have, which language they program in, etc.? People are obviously eager to self-righteously do so at the drop of a hat, but is that really helpful in the modern world (the traditional solution being to wipe out the other small tribe)?